You Can't Talk to AI. Plato Knew Why.

"The agent is drifting, it doesn't understand anything."

No. Your explanation isn't clear.

And this inversion of responsibility, most people will never make it. How many will say "it doesn't understand" instead of "I failed to make myself understood"?

Language Is a Broken Tool

Try describing a migraine to someone who's never had one.

You say "headache". They picture something ordinary. You add "pulsing, unbearable light, nausea". They adjust their mental image, but they'll never see what you're experiencing.

Language doesn't carry experience. It carries a shadow of experience.

And that's exactly what happens when you talk to AI.

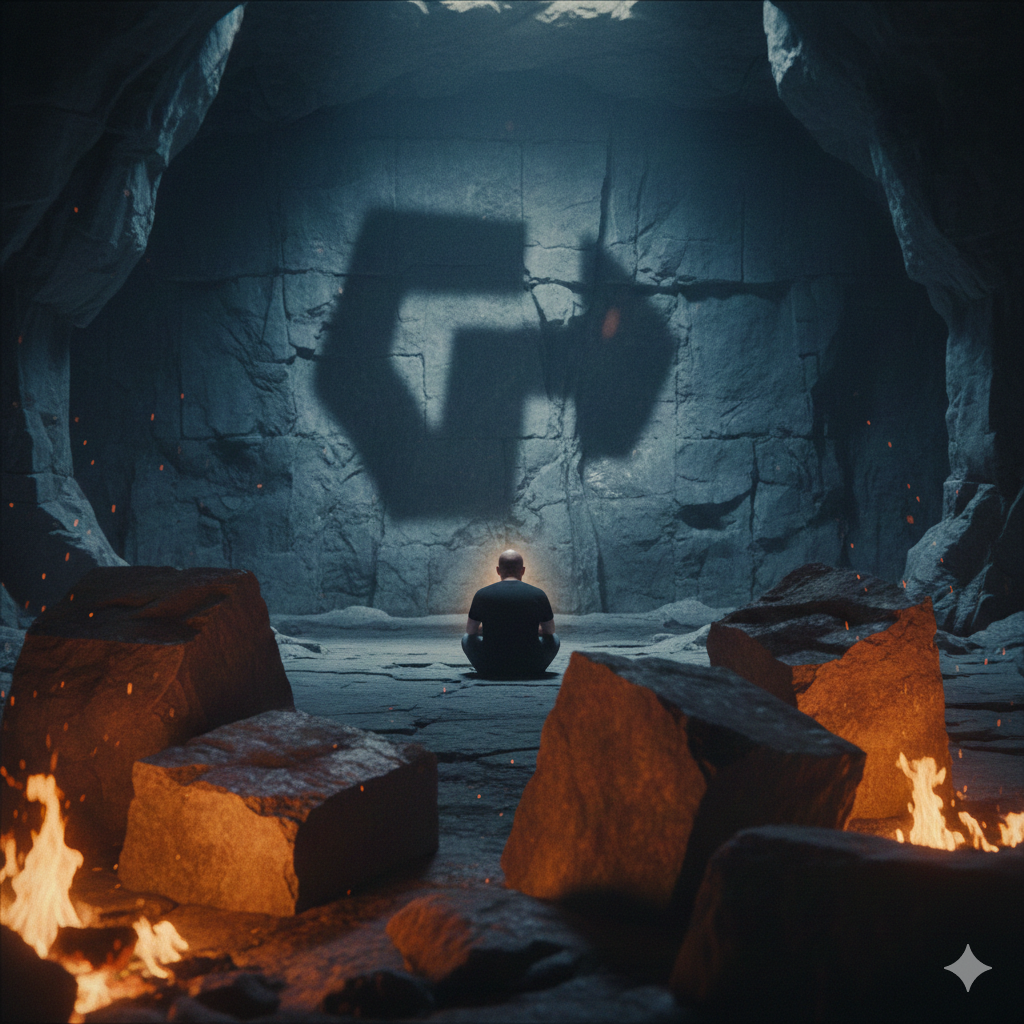

The Allegory of the Cave

Plato understood this 2,400 years ago.

In his cave, prisoners are chained facing a wall. Behind them, a fire casts shadows of objects. The prisoners have never seen the real objects, they believe the shadows are reality.

The one who escapes the cave discovers objects as they truly are. He understands that the shadows were only imperfect projections.

With AI, it's the same.

Your words are shadows. The agent only sees what you project. If your shadow is blurry, its response will be blurry. If your shadow doesn't resemble the real object, the agent will work on something that doesn't exist.

It's not the agent's fault. It's the very nature of language.

The difference between those who stay in the cave and those who escape? The former believe their words are the problem. The latter know their words are only an imperfect projection and work to close the gap.

The Real Lever: Experience, Not Description

People often talk about "better prompting". They're missing the point.

Imagine going to the doctor. You say: "I have pain in my stomach, on the right side."

A bad doctor treats your words. Gives you a painkiller and sends you home.

A good doctor palpates, runs tests, experiences your body and discovers it's your appendix. Not "stomach pain". Your appendix about to burst.

Your words said one thing. Reality said another.

The agent is the same. The real lever is making it touch the problem. Not describing — experiencing. Putting it in contact with reality, not with your description of reality.

A spec like skills, rules, documentation however detailed, remains a shadow. That doesn't make it useless; it reduces the gap between what you mean and what you describe. But it doesn't eliminate it.

Specs are static. Reality moves.

Your CONTRIBUTING.md says "Write tests with Jest", the team moved to Vitest a year ago, but nobody updated the doc. The agent follows your spec, writes Jest tests, and now you maintain two testing patterns. The spec didn't lie. It just stopped being true.

The industry calls this "spec drift." When specs and reality diverge, the agent follows the shadow not the reality.

The way out? Let the agent explore the code, the data, the real context. Take it out of the cave.

And then something unexpected happens, the agent sees things you didn't see. Because it perceives differently. Because it doesn't have your biases, your blind spots, your certainties.

You go from an executor interpreting your shadows to a partner exploring reality with you.

What It Looks Like in Practice

I'm an engineering manager. Hands-on, but still my time for deep technical work is fragmented. Meetings, 1:1s, hiring, strategy. The usual.

A few weeks ago, I needed to set up a CI job to measure test coverage diff on every PR. Not trivial parsing coverage reports, comparing with the base branch, posting results, handling edge cases.

A year ago? That's half a day minimum. Probably a full day with debugging CI quirks.

This time, I gave the agent access to the codebase, the CI config, the existing coverage setup. Not a spec the reality. I let it explore, try, fail, adjust.

Less than an hour. Working. Debugged. Merged.

But here's what matters, during that hour, the agent caught two edge cases I hadn't thought about. It saw the problem more completely than I did, because it was touching the problem, not reading my description of it.

This wasn't a one-off. Around the same time, I built a React Native app in less than 3 days. Not a prototype but a production-ready habit tracker with onboarding, local persistence, stats, and 50+ test files covering real user journeys. The agent didn't just write code, it caught architectural issues I would have missed.

I'm still experimenting. Still learning how far this can go.

Same pattern when debugging a flaky test suite, when reviewing a complex migration. Every time I stopped describing and started showing, the gap closed.

Today, I contribute at a quality level with my teams that I had never reached before. Not because I became a better engineer. Because I learned to let the agent out of the cave.

Why So Few People Get There

In Superforecasting (2015), Philip Tetlock showed that about 2% of people are "superforecasters". Not because they're smarter, because they think differently.

They decompose problems. They revise their beliefs when facing new information. They doubt their own perception. They see the gap between what they think they know and what they actually know.

Communicating with AI demands something similar. Not the same skill but the same posture. The willingness to question whether your words actually carry what you meant. The humility to assume your description is incomplete. The reflex to ask, what am I not seeing?

And like superforecasters, this can be trained. Tetlock proved it. But it requires deliberate effort, constant self-questioning, and a willingness to be wrong.

Most people won't do the work. Not because they can't because it's uncomfortable. It's easier to blame the model than to examine your own blind spots.

The Depth of Change

Michael Arnaldi wrote about The Death of Software Development. He's right. Individuals are becoming exponentially more powerful. The tools have changed everything.

But Michael talks about the what. I'm talking about the who.

The hyper-engineers who master this posture this ability to escape the cave coupled with a strong technical foundation, will create a chasm. Not because they have better tools. Because they see differently.

In Practice:

- Before prompting, ask: "Am I describing a shadow, or showing the real thing?"

- When the output is wrong, ask: "What did I assume the agent knew?"

- After every failure, ask: "What can I let it touch instead of telling it?"

The Way Out

This isn't a skill you learn by reading a Twitter thread. It's a way of modeling the world. Of perceiving the gap between shadows and reality.

Next time the agent "drifts", stop. Don't blame the model. Ask yourself, what did I fail to show? What shadow did I project instead of the real thing?

The door is open. But walking through starts with that question.

---

If this resonated, I write about engineering leadership and building teams at https://www.mathieukahlaoui.com

Discussion